WARLI ART

The Warlis are a tribal community living in the coastal areas of Maharashtra and along the border of Gujarat. Traditionally, they were hunter-gatherers who practiced shifting cultivation and led a nomadic lifestyle. However, with the advent of British rule, new forest laws were introduced, which forbade hunting and shifting cultivation. As a result, the Warlis were severely affected and were eventually pushed into settled rice cultivation.

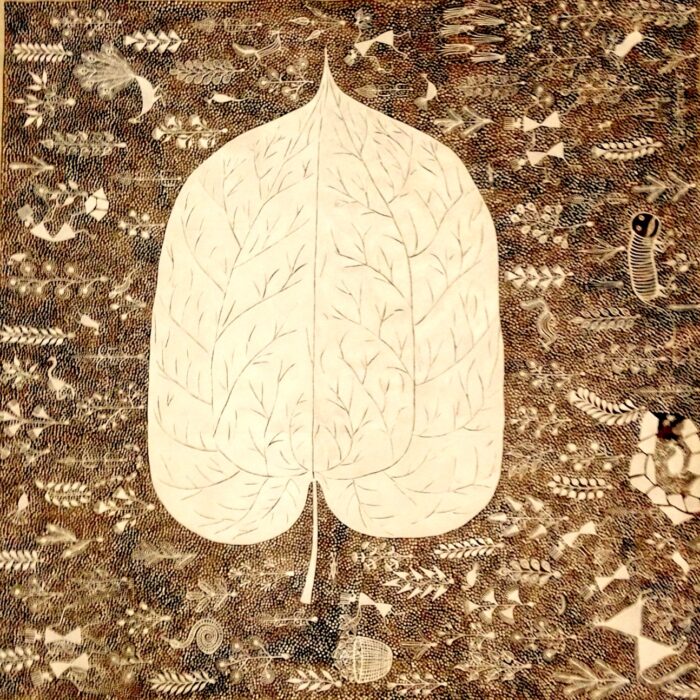

Warli art is deeply rooted in their animistic belief system. These wall murals are primarily created during special occasions such as marriages, childbirth, and harvest festivals. Traditionally, Warli painting is a ritual art practiced by married women. One of the key motifs is the Lagna Chauk (Marriage Square), which is painted on the interior wall of the bride’s house before a wedding. The paint is made from rice paste, and the base is typically a mud wall coated with cow dung or red earth.

About Warli Art

Each ritual painting consists of a square, which is the main motif, and is known as the “chauk” or “chaukat” (square). There are two types of chaukat: Lagnachauk, the marriage square, and Devchauk, the God square. Inside the Devchauk, we find Palaghata, the mother goddess, who symbolizes fertility. The space within the chauk is surrounded by scenes depicting hunting, fishing, farming, festivals, dances, trees, and animals. Human and animal bodies are represented by two triangles joined at the tip—the upper triangle depicting the trunk, and the lower triangle representing the pelvis.

HISTORY

The Warlis did not have a written language until recent times, and their art served as a medium to transmit their belief systems from one generation to the next. Their drawings revolve around the traditions of their community, with themes that include dances, harvesting, children playing, marriage processions, and everyday village activities.

It was only in the 1970s that Jivya Soma Mashe began painting these motifs for artistic purposes. Unlike the traditional ritualistic paintings created during specific ceremonies, Jivya’s works were made to supplement farming income. In doing so, he broke the gender-based convention of Warli art—traditionally practiced by women—and transformed it into a viable source of sustainable livelihood.

Artists such as Jivya Mashe, Shantaram Tumbada, Reena Valvi, and Anil Vangad have since represented Warli art and culture at various international exhibitions held in the USA, France, the UK, and Japan.